West from Kirkby Stephen to pick up the dismantled railway line near Waitby. Along the railway line under Smardale Viaduct to Smardalegill Viaduct. South along a track to Smardale Bridge, then further south to the village of Ravenstonedale. East along minor roads and paths to the A683 at Tarn House, and after a short walk north-east along the A683, east following Tommy Road and a bridleway to the River Eden. North following A Pennine Journey through Nateby and back to Kirkby Stephen. A 14-mile walk in Northern England.

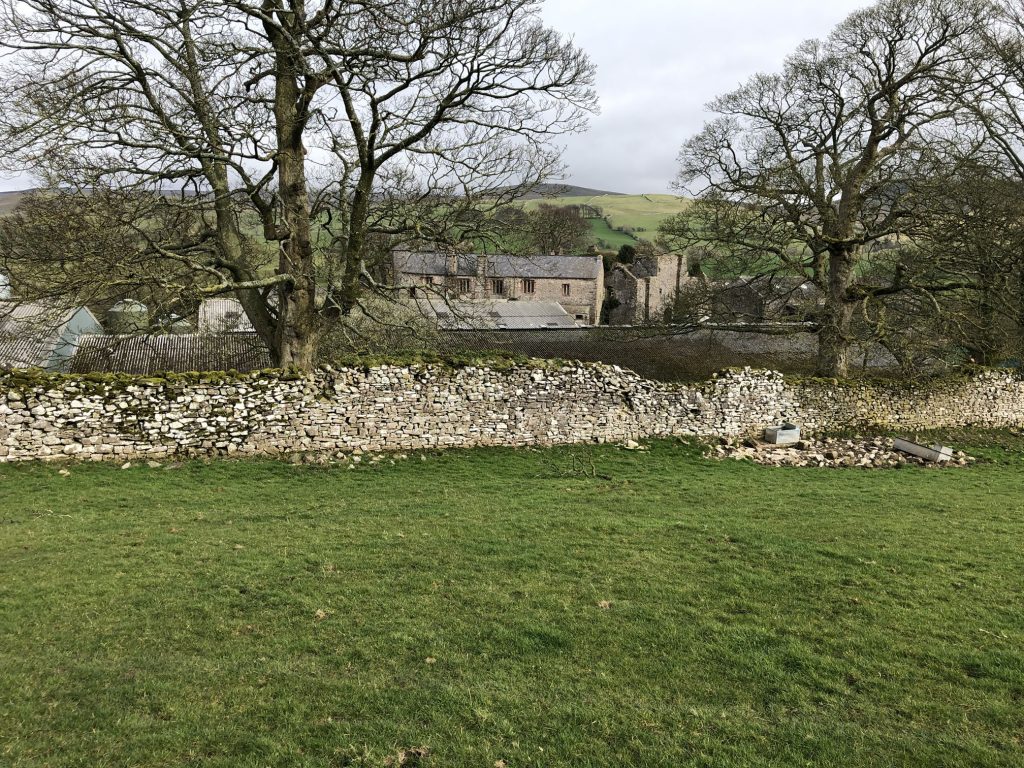

Recommended Ordnance Survey Map

The best map to use on this walk is the Ordnance Survey map of the Howgill Fells & Upper Eden Valley, reference OS Explorer OL19, scale 1:25,000. It clearly displays footpaths, rights of way, open access land and vegetation on the ground, making it ideal for walking, running and hiking. The map can be purchased from Amazon in either a standard, paper version or a weatherproof, laminated version, as shown below.

Standard Version

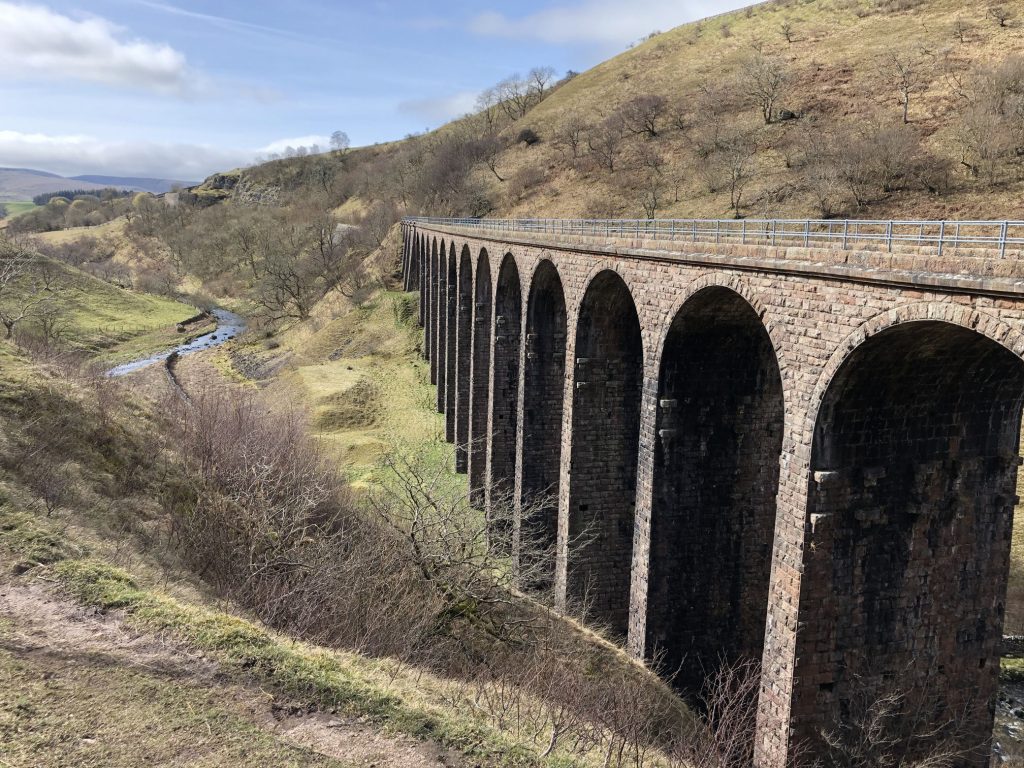

The view north over farmland near Smardale Hall.

The dismantled railway line through Smardale Gill.

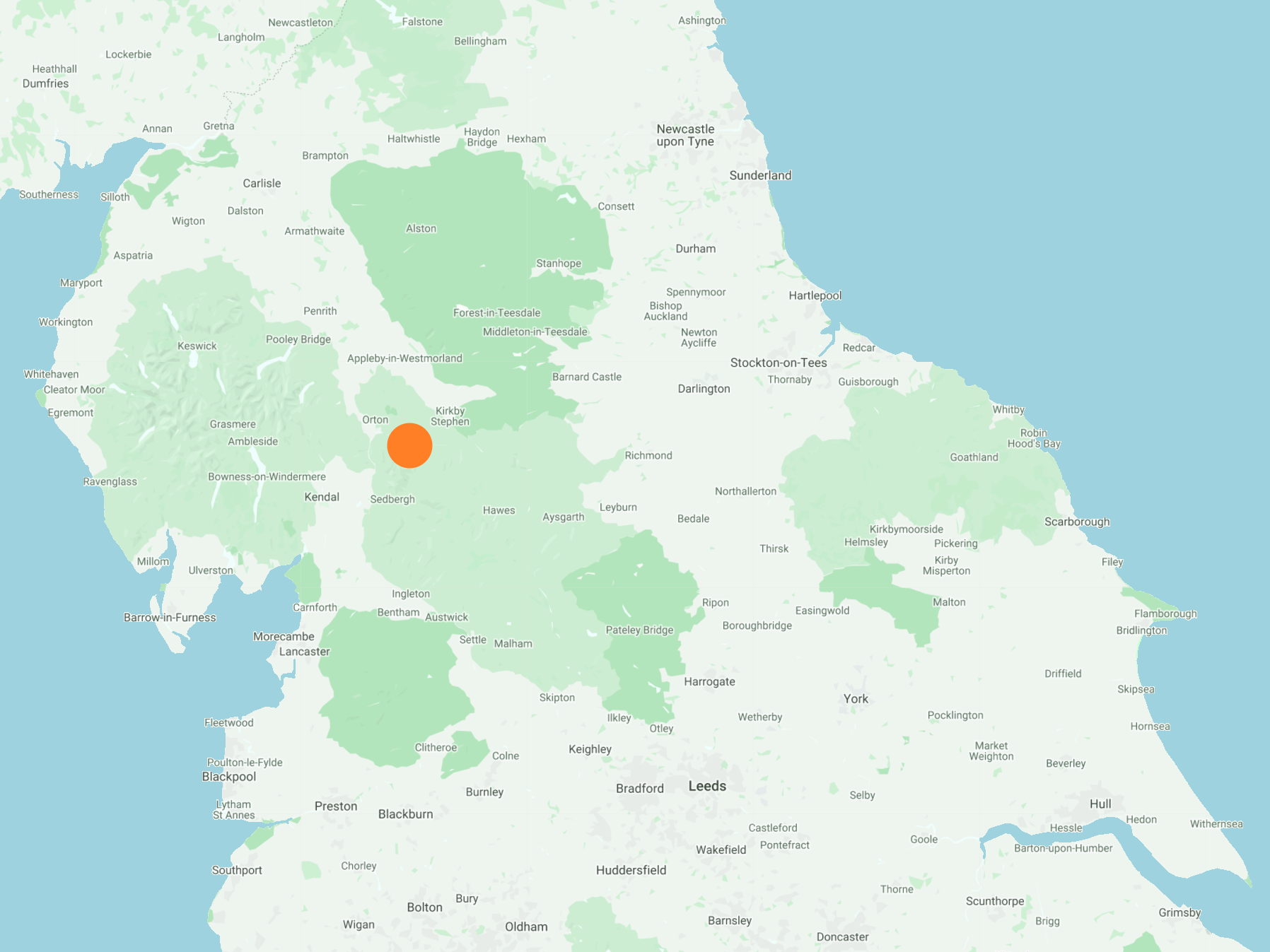

Smardale Gill Viaduct

Smardale Gill Viaduct is a dramatic Grade 2 listed viaduct, 90 feet (27.5 metres) high and 184 yards (168 metres) long, with 14 arches.

The viaduct was constructed in 1861 by the noted Cumbrian engineer, Sir Thomas Bouch, for the South Durham & Lancaster Union Railway. The railway was built across the Pennines to take coke from County Durham to the iron and steel furnaces of Barrow and West Cumbria. At its peak, in the 1880s, over one million tons of coke a year were transported along the line.

The line was closed in 1962 because the Barrow steelworks closed. The Northern Viaduct Trust was established in 1989 to save the viaduct from demolition. Funds were raised to acquire and restore the viaduct, thereby ensuring that it would remain embedded in the landscape, to be enjoyed for generations to come.

Since then the trust has taken over and restored Podgill and Merrygill viaducts on the line east of Kirkby Stephen and has converted 1¼ miles of track bed into a permissive footpath.

Smardale Gill National Nature Reserve

One of the joys of Smardale Gill National Nature Reserve is its easy access. A wide path, of very little gradient, allows visitors to experience a range of truly glorious, unspoilt habitats, from ancient woodland to flower-rich limestone grassland. This landscape also holds interesting archaeology, from the Romano-British times through to the railway heyday. A visit to the nature reserve transports you to a truly remote area of landscape all easily accessible along its 3.5 mile (6 km) length.

The woodlands are ancient and semi-natural, meaning that there has been a constant covering of trees in the area since at least 1600. Within them there is a large amount of dead wood, providing important habitat for a vast number of insects and woodland birds.

The limestone grasslands of the nature reserve are internationally important. Between May and September, they burst into a glorious display of colour as the plants, which are much more abundant than the grasses, come into flower. These include melancholy thistle, knapweed, wood cranesbill, great burnet, northern marsh butterfly, fragrant and common spotted orchid, common rock rose, wild thyme, bird’s-foot trefoil, salad burnet, limestone bedstraw, devil’s-bit scabious, bloody cranesbill and fell wort.

Smardale Gill NNR is well known for its butterflies. The Scotch argus butterfly occurs at the southern limit of its natural range here; one of only two populations found in England. Adults can be seen flying from August to September and feeding on nectar from plants.

The nature reserve also supports the largest colony of northern brown argus butterfly in east Cumbria. It is on the wing during July. Other butterflies commonly seen at Smardale Gill NNR include dark green fritillary, small heath, small tortoiseshell, meadow brown, red admiral, common blue, comma and orange tip.

The river, Scandal Beck, is a tributary of the river Eden and has been designated within the River Eden and Tributaries Special Area of Conservation (SAC). This is due to its international importance for a range of globally endangered species including white-clawed crayfish, bullhead river lamprey, salmon and otter.

Smardale lime kilns

Limestone was probably first burnt in England by the Romans to provide the lime mortar needed for their buildings. But it was not until the last quarter of the 17th century that its use became widespread when increased prosperity led to the building of many of the stone farmhouses and barns which are a feature of the area. The lime needed for this was made in small field kilns, and there are the remains of over 300 in this district alone. Later, towards the end of the 18th century, burnt lime began to be used extensively for arable crops and to improve the quality of pasture land.

Later still, burnt lime was produced on a much larger scale for industrial purposes. The two Smardale kilns represent an interesting stage between the small field kilns, providing lime for local use, and the great lime works of Horton and Langcliffe. They were built to take advantage of the Tebay to Darlington railway line which was opened in 1861 and are contemporary with it. For some years they supplied lime for the steelworks at Darlington and Barrow, but the quality of the lime was considered not good enough and the kilns ceased to operate before the end of the century.

The method of burning was simple, but involved much hard work carting and carrying stone, and the fumes from the kiln could be noxious. The pot was filled with alternate layers of broken limestone and fuel, usually coal, or later, coke. It was lit from the draw hole and allowed to burn slowly at about 900 degrees centigrade for between two and ten days. The burnt lime, or quicklime, was then drawn out and in this case loaded directly onto the railway wagons standing in the siding. If it was to be used for mortar it had to be slaked by pouring water onto it in a mortar pit when it became hydrated lime. For use on the land it was allowed to stand in small heaps to be slaked by rain, or added to large compost heaps after which it could be spread on the fields.

Smardale Gill National Nature Reserve – limestone grassland and flowering plants

The limestone grasslands of the reserve are internationally important. There are two distinctive types.

The mountain hay meadow type contains a distinctive group of plants which is unique to the UK. It is estimated that only 1000 hectares of this type of grassland occur in the world. Between May and September, the meadow bursts into a glorious display of colour as the plants, which are much more abundant than the grasses, come into flower. Some of the flowering plants that can be found include melancholy thistle, lady’s mantle, knapweed, wood cranesbill, twayblade and great burnett. Orchid species include northern marsh, fragrant and common spotted orchids.

Limestone grassland found in this area is dominated by blue moor grass (itself a rare species). Only 60,000 hectares of this type of grassland remain in the UK. This type of grassland occurs on thinner less fertile soils and consequently the vegetation is small and not very productive. It is good to get close to the ground to appreciate the fine detail and diversity of the grassland. Distinctive flowers that can be seen include common rock rose, wild thyme, horse shoe vetch, bird’s foot trefoil, salad burnett, limestone bedstraw, devil’s bit scabious, bloody cranesbill and fell wort.

Grassland areas require management to prevent the spread of scrub and trees which would turn the area into woodland. To do this the reserve is grazed during the winter. This allows plants to flower and set seed during the summer. Scrub is also cut by volunteers during organised work parties to assist sheep in their task.

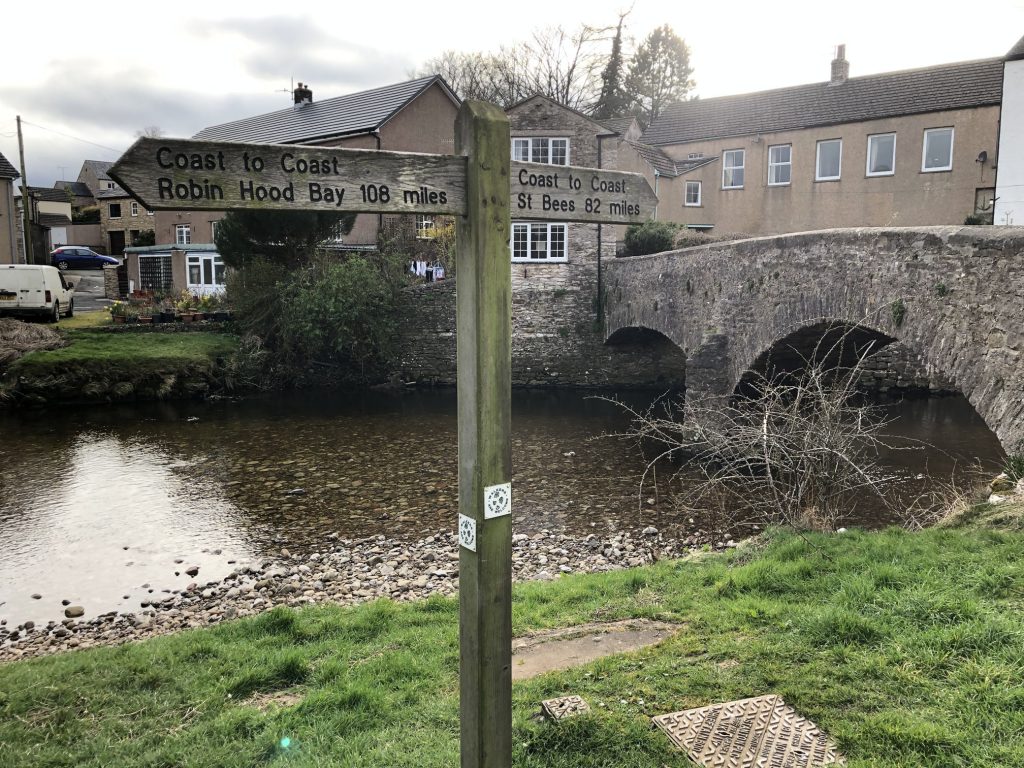

Pack horse bridge built in the 15th century to cross Scandal Beck.

St Oswald’s Church, Ravenstonedale.

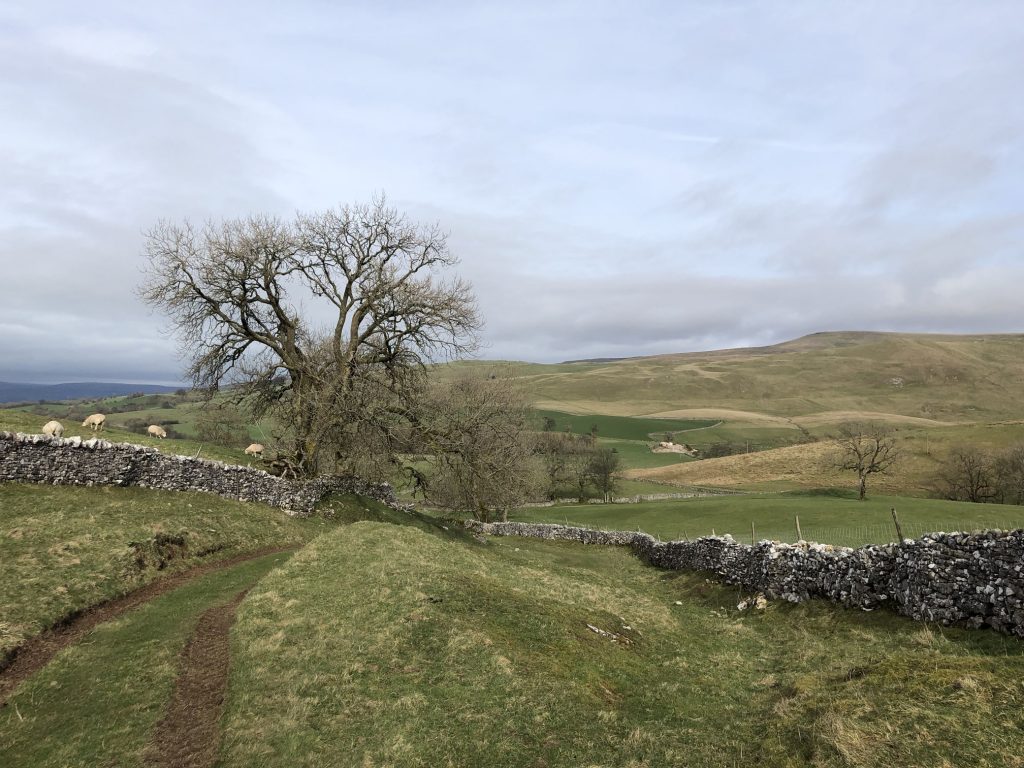

The village of Ravenstonedale.

The Black Swan at Ravenstonedale.

British lambing season

Lambing can start as early as December in some parts of the country, but most farmers will begin in early spring. The sight of lambs scattering the fields is well known as a welcome sight, representing new beginnings and the end of a long winter.

When it comes to delivery, lots of ewes will deliver their offspring unassisted out in the field. But farmers are on hand night and day to keep a close eye in case there are any problems. Some ewes, especially first-time mums, will be brought into the lambing shed to give birth in case they need a helping hand.

How many lambs are born?

The number of lambs born by each ewe varies from breed to breed. First-time mums are more likely to give birth to one lamb, although twins are not uncommon. There are some breeds of sheep that average more than two lambs per litter.

But while lambing is an incredibly intense time in farming, the work starts well in advance. To ensure that their flock will cope with types of terrain or climate, or can produce a specific product, British farmers must carefully examine the characteristics of ewes and rams when preparing the breeding process, adding ‘genetic expertise’ to their broad list of skills.

Tupping

Ewes and rams mate in a process called tupping, which takes place in the autumn. But even before the rams are put to the ewes, lots of farmers are donning their match-maker hats to carefully pair their ewes and rams to create the best offspring. Farmers will use several rams to cover their flock, usually one ram for every 40 to 60 ewes. Using multiple rams increases the chance of ewes being covered by the rams within their fertile period and falling pregnant.

Ewes are only in season once per year, so unlike other animals that become fertile multiple times a year, there is a short time period for them to fall pregnant. There are expectations for breeds like the Polled Dorset, which can get pregnant all year round. Ultimately this is the reason that lambs being born is so intrinsically linked with spring and Easter time. Ewes will normally be two years old before they become a breeding sheep.

Scanning

Like humans, ewes are scanned on farm to find out how many lambs they are carrying. The ideal number of lambs for a ewe to have differs depending on the farming system. Hill farmers prefer ewes to have just one lamb, while sheep in the lowland strive to have twins. It’s not uncommon for ewes to have triplets, quads, or even quintuplets.

Pregnant ewes are often split up into groups at this stage so their feeding and nutrition can be carefully managed. A ewe carrying one lamb doesn’t need the same amount of food as one carrying triplets.

Lambing

Lambs are born around 145 days (4½ months) after the ewe falls pregnant. Lambing can start as early as December and go on to as late as June. Specialist breeds will lamb all year round, satisfying demand for the Christmas and Easter trade.

Depending on the type of farm and where it is, lambing can take place either indoors or outdoors. Often first-time mums will be brought inside to lamb so farmers can keep a close eye on them and give them a hand if needs be. This means that during lambing a farmer will be on hand all through the day and night to make sure things go smoothly.

Feeding

Once the lamb is born, it’s important it gets up on its feet quickly and latches to the ewe’s teat to get the colostrum (first milk) which is packed with nutrients and antibodies. If this doesn’t happen within the first few hours, the farmer will collect the colostrum from the mother and feed it directly to the lamb using a tube.

Adopting

Unfortunately, lambing is a difficult time and not all ewes and lambs will survive, even in the best system. Farmers will pair up orphan lambs with other ewes for adoption. This happens in cases where the mother is unable to look after one of its lambs due to a multiple birth (triplets or quads), or if the ewe or lamb dies.

There are a few ways adoption can take place. Wet adoption is where the birthing fluid from a new born lamb is transferred to the adoptive lamb, so the ewe thinks it is her own. Dry adoption happens when a lamb has died. Skin is taken from the dead lamb and tied to the orphan so the adoptive mother will recognise the scent and take it as her own. Eventually the skin will fall off by which time the lamb and mother will have bonded.

Once the farmer is happy that the lamb is feeding well, they’ll go out into the field which can be like a crèche with lots of other ewes and lambs running around. The ewes can graze on the fresh spring grass which helps them produce lots of milk for their hungry and growing lambs and can be supplemented with a sheep feed to make sure the milk is plentiful. Lambs might also be given special food called creep. It’s put in lamb feeders which are too small for the mothers to get their nose into.

Weaning

Lambs are fitted with identification ear tags which will stay on for the rest of their life. The lambs are normally weaned from their mothers between two and four months old when they will either go on to be breeding sheep (ewes or rams), or they’ll be reared for meat. The ewes then have a few months to get into top condition, ready for Autumn tupping when the process starts all over again.

Visit https://www.countrysideonline.co.uk for more excellent British farming information.

Approaching a tunnel under the Carlisle to Settle Railway.

The track down to the River Eden.

Lammerside Castle, a 12th-century building which was rebuilt and strengthened in the 14th century as a Pele tower, to provide protection against Scots raiders.

Wharton Hall.

Podgill Viaduct.

The view from Podgill Viaduct.

Remains of a railway signal box.

Merrygill Viaduct.

The view from Merrygill Viaduct.

Hartley, just east of Kirkby Stephen.

Frank’s Bridge, Kirkby Stephen.

The River Eden.

Kirkby Stephen.